Imagine you are the Marketing Director of one of the reputed airlines and your airline has frustrated hundreds of passengers due to lack of preparation and poor decision-making in the face of severe winter weather. All other airlines cancelled flights in anticipation of severe weather and returned to normal service within few days. In contrast the airline that you are the Marketing Director of, gave hope to passengers that the planes would fly – yet remained out of service for many days. In short your airline let customers down. Would you focus the blame on external weather conditions or on internal factors relevant to the company’s operation?

If you chose external weather conditions, you should leave your job and join an airline like Air India. You will probably find a lot of like-minded people there. Or may be the organization you work with is like Air India and would not support your decision. But if you chose to focus on internal factors relevant to the company’s operations, consider yourself a brave person, with a good sense of humility, to have admitted one’s mistake. Indeed a very rare thing amongst people and organizations. And if you would have chosen to acknowledge internal factors, not only would it benefit your organization, it would benefit your career too. Let me tell you why.

Says behavioural scientist Fiona Lee and her colleagues say that “Organizations that attribute failures to internal causes make it appear as having greater control over its own resources and future. The public might assume that the organization has a plan to modify the internal features of the organization that may have led to the problems in the first place.”

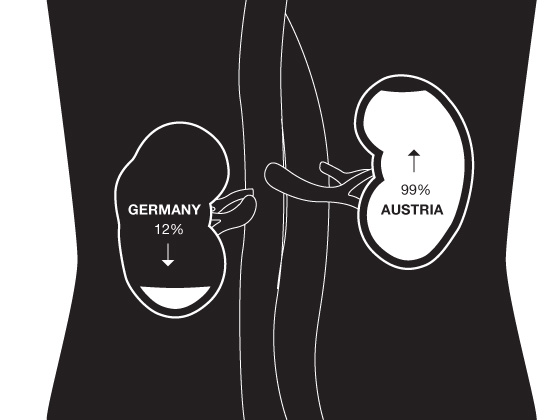

Lee and colleagues have tested this idea by conducting a study in which participants read one of the two annual reports of a fictitious company, both of which explained why the company performed poorly over the last year. For half of the participants, the annual report blamed internal (but potentially controllable) factors for the poor performance and for the other half, the annual report blamed external (and incontrollable) factors for the poor performance. Turned out that the first group viewed the company more positively on a number of different dimensions than did the second group.

Not just that, the researchers collected statements from actual annual reports of 14 companies over a 21-year period and discovered that companies that pointed to internal factors to explain failures had higher stock prices one year later than those that pointed to external factors.

Organizations that attribute failures to internal causes come out ahead not only in public perception, but also in terms of profit line. No reason to believe why it should not work for individuals. So next time you make a mistake, admit it and follow it up with an action plan demonstrating that you can take control of the situation and rectify it.

Source: Lee, F., & Peterson, C., & Tiedens, L. – Mea culpa: Predicting stock prices from organizational attributions – Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 30(12): 1-14 (2004)