There are two schools of thought relating to group dynamics and creativity. One believes in keeping teams constant, believing that the comfort of the team members with each other, makes it easier for them to come up with creative ideas. In contrast, the other school of thought is that mixing team members generates new patterns of thinking.

To find out which one really works, Charlan Nemeth and Margaret Ormiston from University of California conducted a test. Groups of people were asked to think of new ways of solving real problems like boosting tourism in San Francisco bay area. Then team members of half of those groups were kept constant, whereas the other half of the groups had their team members mixed to form new teams. Those that remained together rated their groups as friendlier and more creative. However from the perspective of creativity, the newly formed groups generated significantly more ideas, and those ideas were judged to be more creative.

In another study conducted by Hoon-Seok Choi and Leigh Thompson, three-person groups were asked to think of as many uses as possible for a cardboard box. Then team members of half of those groups were kept constant, and changed just one person in the other half of the groups. When asked to repeat the cardboard box task, analyses showed that the newcomer had helped increase the creativity of the two original team members.

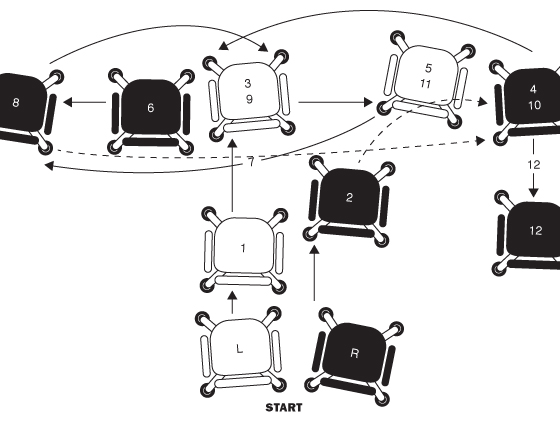

With respect to group creativity, the message is clear: play musical chairs.